If you found an error on this site please let us know by selecting it on the page and pressing Ctrl+Enter at the same time.

Biography

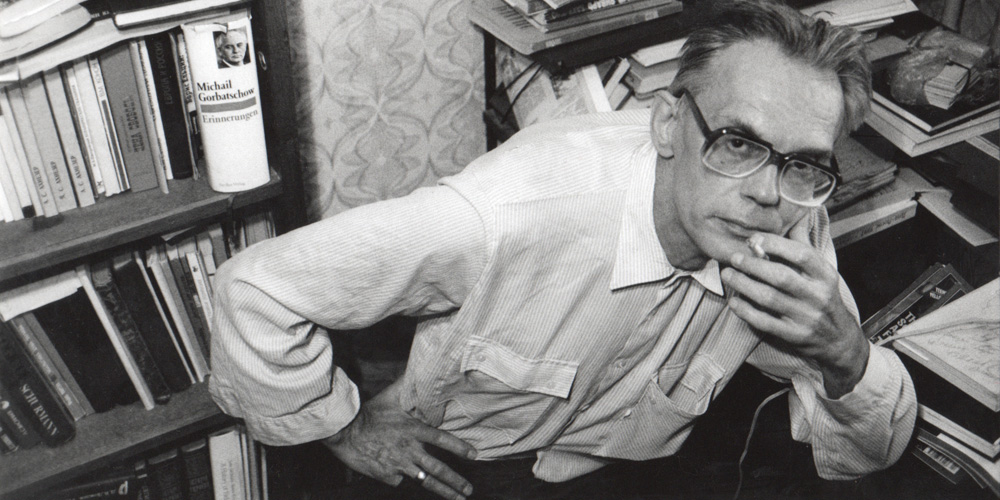

Родился в 1943 г. в Москве. В 1965 г. окончил исторический факультет МГУ.

Дебютировал в печати в 1967 в журнале Новый мир. В 1968—1971 работал на философском факультете МГУ. Публиковался в журналах Вестник Московского университета, Вопросы философии. Перевел письма Юлиана Отступника (Вестник древней истории, 1970, № 1-3). В 1971—1979 — старший научный сотрудник Института международного рабочего движения АН СССР. В 1979—1991 — ведущий научный сотрудник Института США и Канады АН СССР. В советский период работал в области истории и социологии религии, защитив в 1981докторскую диссертацию по теме «Религия и социальные конфликты в США».

Родился в 1943 г. в Москве. В 1965 г. окончил исторический факультет МГУ.

Дебютировал в печати в 1967 в журнале Новый мир. В 1968—1971 работал на философском факультете МГУ. Публиковался в журналах Вестник Московского университета, Вопросы философии. Перевел письма Юлиана Отступника (Вестник древней истории, 1970, № 1-3). В 1971—1979 — старший научный сотрудник Института международного рабочего движения АН СССР. В 1979—1991 — ведущий научный сотрудник Института США и Канады АН СССР. В советский период работал в области истории и социологии религии, защитив в 1981докторскую диссертацию по теме «Религия и социальные конфликты в США».

Научная деятельность

С начала 1990-х изучал становление и развитие политических режимов, проблемы демократии, авторитаризма и воспроизводства власти на пространстве СНГ. Публиковался в журналах Век ХХ и мир, Свободная мысль, сборниках Иного не дано, Осмыслить культ Сталина и др. Возглавлял Центр эволюционных процессов на постсоветском пространстве.

Dmitri Yefimovich Furman about himself

Interview for the book ‘D.Y. Furman. Selected Works’

The Territory of the Future 2011.QUESTION: Dmitri Yefimovich, you appear to be one of the few Soviet and post-Soviet scholars who hardly experienced any impact of Marxism. One does not find it ( apart from almost ritual quoting of the classics) even in your juvenilia. How can you explain that?

ANSWER: I am afraid there is no comprehensive and accurate answer to this question – too many factors influence our personal development. Still I can assume that childhood ideological impressions definitely played their role. I was brought up by my grandmothers, my mother’s mother and her sister, thus it is they who are my family in the first place, and to some extent their mother whom I have still found alive, but also their brother Boris Vladimirovich Ioganson who in 1950s – early 1960s presided over the Academy of Arts and was a true honor to his family. The family was aristocratic and bourgeois, my great-grandmother was remembered even to dance with the sovereign emperor at Smolny prom as the best student. As I see it now the family ideology used to be common for a vast social stratum. They naturally hated the Revolution but perceived it as some inevitable recurring natural disaster. Revolution is always blood, chaos and ‘domain of boors’. But as soon as it’s over, it all calms down and life resumes its normal course. Russia turned queer, acquired some taint of awkward Jewish ideology, still it was the same old Russia, and members of that stratum with little or even no remorse changed sides beginning to serve the Soviet regime. My grandmothers’ brother Boris Ioganson used to bear arms in Kolchak’s White Army for quite a time, but after Kolchak was defeated he somehow joined the Red Army. Before the Revolution he had studied art under Konstantin Korovin, so in the new Soviet surroundings he found himself in the realm of Socialist Realism becoming its classical representative. He was in the White Army but painted ‘Interrogation of the Communists’. I don’t think he suffered much from ideological torments – Russia remains the same as well as Russian rulers, ideologies may change, but Russian artists have to celebrate Russian rulers and ideology they preach. To me it seems very similar to that solid and profound ideology of the Mikhalkov family who genuinely see nothing disgraceful about the Russian nobleman first writing the lyrics of the Soviet anthem and then of the anti-Soviet one. Religion played no significant role in this ideological system. In official nationality triad ‘Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality’ orthodoxy appeared to be the shallowest component.

It is from my grandmothers that I got the first and strongest, if I can put it this way, sociological insight. I even remember the circumstances under which my grandmother uttered the words I would never forget. She was accompanying me to school, and as we were crossing the traffic road all of a sudden I asked her: ‘Grandma Lida, is Stalin the tsar?’, and she replied seriously as if talking to an adult who was quite aware that they shouldn’t have touched upon that topic: ‘Yes’. I suddenly realized the difference between form and substance, forms vary but the substance is the same, I never discussed it with my friends, but gave it much thought.

PERESTROIKA AS SEEN BY A MOSCOW HUMANITARIAN

ABOUT PERESTROIKA: TWENTY YEARS AFTER

Gorbachev Foundation 2005My participation in the political life of the era of Perestroika was minimal. Moreover, I did not know personally at the time any of the more prominent political figures of that period.

I met many of them, including Gorbachev, later. That is why my memories of Perestroika are the recollections of an ordinary and not very active participant in the events, a member of the Moscow humanitarian intelligentsia.

1. Pre-Perestroika Era

Marxism-Leninism died a quiet death that went unnoticed at some moment in Brezhnev's times. During Khrushchev's era and at the beginning of Brezhnev's era, I met very many Marxists who were bright and really committed. They all, naturally, were opposition-minded.

That was the time when showing interest in Marxism and being in opposition were practically one and the same thing. One and the same process repeated itself time and again, when someone from the great mass of people with formulas of official ideology drummed into their heads would go back to its «original sources» to get astonished at the discrepancies between what had been written by the «classics of Marxism» and the official orthodoxy and «real Socialism.» If a person becomes convinced that he or she understands the truth contained in the sacral sources of ideology abandoned by the government and not understood by society, they would have a natural desire to open people's eyes to it. The official Marxism logically gave birth to its own «Protestantism.» However, Marxism is also an ideology of historical optimism and action aimed at changing the world. That is why the realization of the existence of a conflict between the official doctrine and the contents of Marxist texts inevitably resulted not just in the desire to «open people's eyes», but also in the drive to change society, the drive towards «Perestroika.»